The Judge Advocate General: Soaring to the Top

The first Chinese American to attain the rank of General Officer in the U.S. Army passes down to his children his beliefs in America, opportunity, and family.

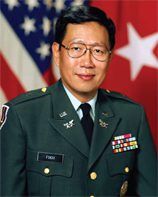

Major General John L. Fugh, U.S. Army (ret.)

There’s no question that John L. Fugh, retired major general in the U.S. Army, has attained a prominent status in America. General Fugh was the first Chinese American to reach flag rank in the U.S. Army. As the Judge Advocate General, he managed the Army’s worldwide legal organization, overseeing 4,700 active duty, reserve, and civilian lawyers and more than 5,000 paralegal and administrative personnel, in addition to serving as the legal advisor to the Army Chief of Staff for the Persian Gulf War. After retiring from his post in 1993, he became partner at the Washington, D.C., law firm of McGuire, Woods, Battle & Boothe. He later served as president of McDonnell-Douglas China, then joined Enron International China, where he served as chairman.

In addition to having been the top uniformed lawyer of the Army, General Fugh has received numerous awards, including the Bronze Star, Legion of Merit, Defense Superior Service Medal, and Distinguished Service Medal. Last January, he was awarded the Outstanding American by Choice Award for his keen commitment to this country. Currently he serves as chair of the Committee of 100, a nonpartisan national organization that promotes constructive and positive relations between the United States and China and encourages Chinese Americans to participate in all aspects of American life. Not only has General Fugh had a lifetime filled with achievements, but his fierce commitment to improving Asian American relations remains strong. Furthermore, he is universally respected among politicians and legal professionals.

General Fugh’s two children— Justina Fugh, 46, senior counsel for ethics at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Jarrett Fugh, 42, partner at Thelen Reid Brown Raysman & Steiner in Los Angeles—are both accomplished lawyers. Like their father, they attended George Washington University Law School and moved into the legal industry, where they have achieved success. Justina, whom her parents initially wanted to name “Justice” as a tribute to their fierce belief in America, provides ethics counseling to EPA employees, steering them away from conflicts of interest and ensuring that their conduct as government employees meets the highest standards. After graduating from Duke University at age 20, Jarrett went on to law school and later made partner at his law firm at the young age of 33. Jarrett continues to make his mark by representing U.S. and international clients in real estate, hospitality, and financing transactions.

Influence and Impact

One might assume that Justina and Jarrett’s career choices were a direct result of having a father with such a prominent status. But ask either of the Fughs how much of an impact General Fugh’s high-level position had on their choices, and both will say that it wasn’t particularly relevant. In fact, the two weren’t even encouraged to become lawyers. More significant, they believe, was a combination of family support, a strong work ethic, a belief in America, and a dash of luck.

Justina Fugh

Photo courtesy of US EPA

“Growing up, he was just Dad,” Justina reflects. Indeed, General Fugh may have been soaring through the ranks as an Army official while they were growing up, but his status was barely acknowledged within the household. He was firmly grounded in the family unit, one that was primarily run by his wife, June. “Mom was the stalwart in the family,” Justina says. “Dad was in the Army and that meant he went to work all the time and my mom ran the house.”

Not only was June the anchor of the family, but she played a key role in her husband’s success. “I don’t think I would’ve done as well in the military without her,” General Fugh says. “She was a big supporter. She’s a big factor in my life. She gave up her career as a scientist and traveled with me around to different military assignments. She’s also a lot smarter than me. She’s more competitive than I am and she egged me on. She’d say, ‘Yes, you can do it.’”

An Accidental Path

General Fugh’s career path, which elevated him to such heights, was not exactly predestined. It was the culmination of a series of events that led him down that road. To begin with, his citizenship status got off to a shaky start. “[My mother and I] came [from China] in 1950 as temporary visitors,” he explains. “In those days, the immigration policy was very severe. Only 100 Chinese immigrants [per year] were allowed to come to the States. It was a private bill passed by Congress that made us permanent residents. In 1957, I was naturalized as a U.S. citizen.

“When I first arrived, I spoke very little English and I was not that familiar with the culture. There was a deep sense of dislocation, not knowing what my future would be,” he explains. “At first I thought one day I’d go back and get into foreign service in China, but then things changed drastically. Upon graduating from Georgetown, I was about to be drafted.” Ironically, he notes, he was not eligible to join the ROTC because he was not a U.S. citizen, and yet he was eligible for the draft.

Fugh was issued a student deferment and chose to attend law school despite having been strongly discouraged by friends and family who, in 1957, thought it unlikely that clients would choose to see a Chinese lawyer. But for his own reasons, he chose to enter the law. “I’m very bad in science and math,” he says with a smile. “I went ahead anyway. I figured, What else can I do?”

A Career Takes Flight

Though he may have fallen into the practice of law, General Fugh’s career success was no accident. Once he began his journey, determination and a commitment to his work propelled him toward the top. He pushed for opportunities to shine. Though Army personnel were reluctant to send him on an assignment in Taiwan because his Chinese heritage raised a red flag about his loyalty to America, he didn’t let that deter him. Neither did his wife. “June went over to see the number-two JAG general at the Pentagon—who was very enamored with everything Chinese—and I did get the job.”

That proved to be a strategic move. The person he replaced there was a full colonel. Fugh came in as a “young whippersnapper in my first staff judge advocate job” and made an impression by doing all sorts of things the higher-ranking colonel had neglected to do. “That was the beginning. Ever since then, I’ve never been a deputy; I’ve always been the top legal officer,” he notes.

General Fugh believes that his minority status may have added to his career momentum. “As a minority, I feel that if you do well, it’ll stand out,” he says, noting that if you don’t, that too will stand out. “When I was on active duty, there were only two other Chinese Americans—one colonel and one lieutenant colonel,” which made it even easier for him to stand out.

The Fugh family at an annual gathering in Virginia Beach, August 2007. From left: Jarrett, Isabelle, Tracy, John, Jeremy, June, Joshua, Jonathan Frenzel, and Justina.

Ethnicity Emerges

General Fugh says that his run-ins with ethnic discrimination were limited. One incident he recalls occurred during his attendance at Command General Staff College. “I found a slip saying I was excused from [one course of instruction],” he says. Concerned that he wouldn’t complete the necessary coursework, he went to see the security officer. It turns out that because Fugh spent the first 15 years of his life in China, it proved difficult—and expensive—to complete a thorough background check and grant him security clearance, so administrators decided to waive the course requirement for him.

The issue of security reappeared during his term at the Army War College, where students must be cleared for the highest level, higher even than top-secret clearance. Though most of his peers had reached that level early on, he lagged behind. Just as he had fought for the assignment in Taiwan, he spoke up for what he believed in. “Don’t waste taxpayers’ money and send me to the U.S. Army War College if I’m missing a big hunk of instruction,” he thought. “So I made a big issue out of it at the Pentagon.” He was granted clearance. A lesson he took away from these experiences was that many decisions are made arbitrarily and a little extra pushing can go a long way.

Though General Fugh occasionally heard ethnic slurs— particularly following the Korean War—and sensed some racially charged behavior, he says that it was typically directed at others. His personal experiences revolved around being perceived as a curiosity, such as one incident in Georgia in the 1950s when a local store proprietor asked if he was a genuine Chinese person. “[He’d] never seen one,” he explains.

Yesterday and Today

“It was never an emotional issue for my father,” Justina says of discrimination. “In my presence, when it was discussed, he’d talk about it nonemotionally.” This had a clear impact on her perceptions of discrimination as a career obstacle: it wasn’t considered one. “We’re really good assimilators and I think of myself as an American,” she says. “We have a pretty high-achieving background. Everyone does great things, so of course [that’s what I expected of myself]. I just figured you could do anything you wanted.”

Justina also points out that from her perspective, being Chinese and being a woman translates into strength and accomplishment. “There’s this stereotype of a submissive Asian woman. My father has three sisters and my mother has four sisters and I’ve never seen that.” Justina also recalls her father’s amusing comments about June’s prominent family role. “He believes in America,” she says. “He believes in one man and one vote. And he always said, ‘In this family, June’s the man and she has the vote.’”

Being a minority professional hasn’t entailed any particular obstacles for Justina. “But I will say that I’m more conscious of being Chinese and a minority at the EPA, because we do a lot of diversity benchmarking.” In her senior role, she has become more sensitive to issues of race and ethnicity, realizing that she has a responsibility to others. “Other people, maybe not me, look to people in senior positions who are minorities and say, ‘If she can do it, so can I.’” Justina takes this role seriously and has chosen to be a mentor to both Asians and non-Asians, including one colleague whom she taught to think outside of the parameters set by others. “We had incredibly inspired sessions about being more than your environment perceives,” she says.

Jarrett Fugh

Jarrett, too, has had a notable lack of minority-specific challenges. “It really hasn’t had that much of an impact. When I joined Thelen out of law school, we didn’t have a high number of attorneys of color, but I never felt isolated. [Now] I work with Asian and non-Asian clients,” he notes. Unlike his father, he doesn’t feel that he has benefited from being a minority. “I haven’t seen it as a plus or a negative,” he says.

Though it was only on the periphery as she was growing up, Justina is now acutely aware of her father’s approach to the law. “I admire so much of what he’s done by putting the law first and ethnicity second,” she says. “It really is more important what the law is and how people interpret the law. You’ve got to get the law right. I have trouble with people who put race and diversity first. We don’t do that.”

The Message Trickles Down

Despite his superior military ranking, treasure trove of awards, and renown, General Fugh remains an unassuming person who at times downplays his success.

“I was in the right time at the right place,” he says of becoming the first Chinese American major general in the U.S. Army. “There are not that many Chinese Americans in the military services. I’m just lucky to have come along, to climb and to make it to the top.” That’s not to say he doesn’t acknowledge his performance. “It was luck plus hard work. You have to do well at what you do.”

This same message was passed along to his children. Rather than pressuring them to attain any particular status or follow any predetermined career path, he impressed upon them the importance of doing their best in whatever form felt right for them. In fact, Justina and Jarrett weren’t even encouraged to become lawyers.

“My wife and I had the view that they should do what they want to do,” explains General Fugh. “We never encouraged or discouraged them. You’ve got to do what you believe is right. We’ve tried to give them a sense of balance in life and try to avoid the extreme.”

General Fugh serves as chair of the Committee of 100, a nonpartisan national organization that promotes constructive and positive relations between the United States and China, and encourages Chinese Americans to participate in all aspects of American life.

And yet, they both entered the field of law.

Perhaps it’s the result of having parents with a strong belief in justice and a commitment to the greater good. Or maybe it has more to do with the apple not falling far from the tree. “I liked the idea that I wanted to emulate my dad,” admits Justina. “There’s also an aspect of wanting to be God’s little policeman.”

“I’m a combination of both my parents,” says Jarrett. “Like my father, I have a lot of energy and always stay active. I think that intellectually, however, I am more like my mother. My social traits are definitely from both of them, as they are very skilled social people. You don’t rise to the level of my father without both of my parents having accomplished social skills.”

Indeed, General Fugh’s sociability is strongly evident. Justina and Jarrett often run into people who recognize the name Fugh and ask if there’s a relation. “When that occurs,” notes Jarrett, “the person asking about my father will inevitably say something like, ‘Your dad is a great guy’ or ‘I’m a big fan of your dad.’ It’s uncanny. He was just born to be likeable.

“But that’s just one of the factors. He’s a smart guy, extremely hard-working, and he had a certain amount of luck,” Jarrett says, adding one more thing: “My mother also played a huge role in my father’s achievements. He often says that he would never have gotten to where he is without her.” DB

Kara Mayer Robinson is a freelance writer based in northern New Jersey.

From the May/June 2008 issue of Diversity & The Bar®