Annual Report on Firms with No Minority Partners

| Diversity & the Bar® thanks the firms who took time to respond to our inquiries and candidly discuss their plans to address their lack of diversity. It is encouraging to hear the issue is a priority. However, there were several law firms who did not respond to our requests to be interviewed. We invite those firms to contact us and let us know what steps they may be taking to build a more diverse and inclusive workplace. Diversity & the Bar would love to publish a follow-up article and report on future success stories. |

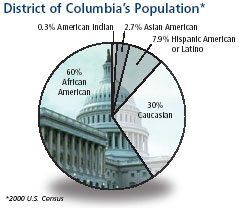

As the nation's capital, Washington, DC, is known for many things: the White House, the Smithsonian Institution, national monuments and museums, cultural events and organizations, and diversity. According to data from the 2000 U.S. Census, 60 percent of the District of Columbia's population is African American. Of other minorities, 2.7 percent of residents are Asian American, 7.9 percent are Hispanic American or Latino, 0.3 percent are American Indian, 2.4 percent are two or more races, and 3.8 percent are a race not specified on the Census. Slightly more than 30 percent of the population of Washington, DC is white.

But you might not know that by visiting a partner's meeting at many of Washington, DC's law firms. Several firms—from small offices with 11 to 25 attorneys to larger firms with up to 100 attorneys—do not have partners of color. A handful of firms do not have female partners. These facts come from data supplied by the firms themselves each February for the National Association for Law Placement (NALP) annual law firm questionnaire, which NALP makes available online (www.nalpdirectory.com) and in print for students and others looking for jobs in law.

This year, 1,597 private firms nationwide—including 139 with offices in Washington, DC proper (not the metro area, which includes Northern Virginia and parts of Maryland)—filled out questionnaires. Included in the questionnaire is demographic data for partners, of counsel, associates, senior attorneys, staff attorneys, and summer associates.

Of the 139 District of Columbia law firms that filled out the NALP questionnaire, 33 firms did not have partners of color in their DC offices (see sidebar). Of those firms:

- 10 firms were in the category of 11 to 25 attorneys;

- 11 firms were in the 26 to 50 attorneys category; and

- 12 firms listed 51 to 100 attorneys.

Although their numbers are low compared to men, women fare much better than minorities in terms of partner demographics in Washington, DC offices. Five firms across all categories—Debevoise & Plimpton, Dykema Gossett, McKee Nelson, Proskauer Rose, and Willkie Farr & Gallagher—had no female partners as well as no partners of color. One firm—Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison—listed an African American male partner but no female partners.

Diversity & the Bar® chose to focus on Washington, DC because it is the nation's capital, is known to be diverse, and is the center of politics and government in this country. We also chose to contact only the firms in the category of 51 to 100 attorneys in order to avoid having firms use size as a reason not to have a diverse partner demographic.

So how do these firms explain why, in this day and age, their partnerships are so much less diverse than the city they call home? Some firms did not return repeated telephone calls. But those who did point to a variety of reasons for their lack of diversity at the partnership level, including: the specialty area of the firm; the lure of corporate and political careers to attorneys moving up the ranks; and—with several top universities and law schools in close proximity—the fierce competition for top minority law school graduates. In the DC office of Willkie Farr & Gallagher, the partners are all white males, according to the NALP data, which was verified by the firm. "We hate that statistic," says Shelley Chapman, partner in the New York office, who also chairs the women's practice development committee.

Within the past two-and-a-half years, Willkie Farr & Gallagher's DC office has experienced a "growth explosion," says Chapman. Lateral partners have brought new practice areas and new clients, as well as expanded other practice areas, she explains. "They have barely been able to catch their breath," she says. But, Chapman adds, "they have always been aware of their 'bad numbers' and have been reaching out in many ways to try to do what they can to improve."

During the summer, three women partners in New York went to the nation's capital to talk about how to recruit and retain more female attorneys. As a result, the firm has institutionalized a part-time flex policy in the DC office, which includes a continuous track to partnership. "You don't have to come back full time to be considered for partner," Chapman explains. "It is possible for you to work part time and not lose your place in the class."

This may help retain and recruit women, but what about partners of color? Kim Walker, director of diversity initiatives for the firm and chair of the diversity committee, says some attorneys in the DC office are on her committee, and they have been contributing ideas. One was a gathering of minority law students from DC law schools, including Georgetown University and the historically black Howard University. Two of the four who visited the DC office are now summer associates there. "We plan to do that every year," says Walker, who is African American.

In the past, the New York and DC offices did not communicate much, she adds, even though the diversity initiative has been in place since March 2003. One priority is bringing the DC attorneys further into the fold and another is creating a diversity web site, similar to what the New York office has, says Walker. "We're working very hard to do this in tandem," she adds.

This past spring, Chapman and Walker also brought in a consultant to perform diversity training required for every attorney in the firm, including in Washington, DC. Chapman calls it eye-opening. "White men were saying, 'We've been taught for all these years to treat everyone the same.' That's right, but you have to be able to see the differences, and sometimes trying to treat them the same means treating them slightly differently," she says.

It will take time for the DC office to wrap itself around the concept, says Chapman. But with her and Walker in New York continuing the dialogue, she says it will happen. "You need to get some momentum going," she adds, using New York as an example of what success can look like in Washington. "We've done that in New York with women and now we've got a really great group of women who have succeeded on all kinds of paths."

Women also have made strides at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, according to Kyle Drefke, hiring partner for the DC office, and Lorraine McGowen, an African American partner in the New York office who also chairs the firm's diversity committee. One of the two female partners in DC, Felicia Graham, is the partner-in-charge of the office. McGowen is head of a practice group and the head of another practice group in San Francisco. "We have real people in leadership roles who can be mentors," says Drefke. But while he admitted that the number of female partners (two) and partners of color (zero) in the nation's capital are poor, he cites the demographics of Orrick's associates: Twenty percent are minorities and 44 percent are women.

So how to retain these minorities and women and add to the numbers? McGowen says the firm is working with headhunters to hire diverse lateral partners. But, she adds, "The DC office is smaller and the practice areas there are more limited. You're looking for lawyers that have national experience in those areas—we wouldn't bring into any office just any type of practice."

According to McGowen, the diversity committee also has initiated a firm-wide mentoring program, participates in pro bono and community activities, and offers seminars on professional development for new and mid-level associates. "It's not solely for diversity reasons, but it helps to create a pathway for all associates," she adds.

Additionally, McGowen conveyed that on the recruitment side, the firm also is working on connecting more closely with minority student associations at law schools. Some of the firm's associates are on the regional board of the National Black Law Students Association. Attorneys participate in seminars, and sponsor and attend events and job fairs. She also stressed that this fall the firm will host a regional meeting of the National Black Law Students Association.

As indicated by Drefke, focusing on students is important to the firm's culture and processes. "We don't hire very large summer associate classes in the hopes of whittling those people down over the years. We try to hire a modest number of people, and we invest time and energy in them to become our partners of tomorrow," he says.

Drefke indicated that competition is tough, which means the best students and attorneys have the most options. "If you have strong lawyers who are great personalities, they are attractive to all kinds of groups," including other firms, corporate legal departments, government, and the non-profit sector, he says. But, Drefke adds, "It's rare someone leaves our firm and goes to another firm in Washington. Too often, people go on to other opportunities in other areas."

McGowen says she has seen more women and attorneys of color move into the firm. "The number of minority associates has drastically increased as we've grown in practice areas," she explains. "When we first opened, it was a challenge to recruit any associate because our focus was so narrow. As we've expanded, it gives our associates much more opportunity."

Over the past two years, Jenner & Block has seized the opportunity to increase diversity among its attorneys, says Donald Verrilli, partner in the DC office and chair of the firm's diversity committee. "There's been a gathering sense in the firm that we really need to take the bull by the horns and be very proactive," he says, adding that there are some partners of color in the firm's Chicago office and several mid- and senior-level associates of color who should make it to partner in DC. "We've always felt we had positive intentions and values, but that's not enough. You really have to act on them and that's what we're about doing right now."

Last year, according to Verrilli, the firm reinstituted its diversity committee and began focusing on entry-level hiring by expanding to additional law schools for recruiting and working with individual professors to identify candidates. The firm also is "aggressively" reaching out to organizations within the law community that advocate for diversity, and getting Jenner attorneys involved in their activities.

"We're starting to see some positive results in entry-level hiring, but we realize the second phase is retention," he says. "We've got to get people in the door, but it's critical we retain the diversity of the associates we recruit."

—Donald Verrilli

That comes with a strong firm mentoring and professional development program, Verrilli adds, which will help all associates. He also cites the most recent Vault survey, "The Best 20 Firms to Work For," that shows Jenner scoring among the top 10 firms in overall associate satisfaction, including on diversity. "That shows we are committed to ensuring our professional culture is one that is inclusive and focused on the importance of diversity," he adds.

With the new initiatives, partner demographics should change, Verrilli continues. "That kind of culture change is not going to pay off in larger numbers instantaneously, but we believe it will pay off in the medium and long term."

At Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, partnership is structured differently from other firms, according to Michael Mazzuchi, hiring partner in the Washington, DC office. Partners are on a tiered system of compensation, meaning partners on the same level of seniority are compensated the same—not based on billable hours, contracts, or other methods that other law firms use, he explains. "As a result," he adds, "partnership decisions are much more carefully made here. There is less flexibility about them."

According to Mazzuchi, Cleary Gottlieb also does not hire laterals. "We have a much older model of what it means to be a partner, and as a result, I think our firm is institutionally slower to change."

That doesn't affect minority associates more than other attorneys, he notes, but could be one explanation for the lack of partners of color in the DC office. What about competition for top minority candidates? Mazzuchi says competition cuts across demographics. "What we try to compete first and foremost in is being the best professional environment for the lawyers. We're recruiting as individuals, not as members of any minority group," he says. "Our hope is that minority candidates find that appealing just like anyone else."

But Cleary Gottlieb does recognize its need to beef up the numbers, and, therefore, has instituted a mentoring program for all associates so they can gain stronger footholds in the firm, Mazzuchi indicates. The fact that there are no partners of color in Washington, DC could be a deterrent, he admits. "If someone were looking for another minority lawyer in a senior role to be part of their professional development, that's going to be a difficulty someone would face here, since we don't have any minority partners here."

Mazzuchi says the firm wants partners of color in Washington, DC. But, as stated by Mazzuchi, the firm is not considering making a lateral hire simply because a candidate is a minority. "The partnership structure doesn't lend itself easily to that. I don't know that that's consistent with the goals of this firm," he explains.

So how, then, can the firm meet its goal of a more diverse partner demographic in the nation's capital? "I'm not sure that the goal of making minority candidates partners is different from the goal of making anybody partner," Mazzuchi answers. "We strive to have a firm where people are happy, successful professionals. I want our firm to have partners of color and when we do, I want those people to have gone through all the same experiences I did [to make partner]."

In Washington, DC, though, the lure of other opportunities is strong, explains Vernon Francis, partner in the New York office of Dechert and co-chair of the firm's diversity committee. "You get good people and they go on to do bigger and better things," says Francis, who is African American. One black partner in Washington, DC left the firm to work for the Securities and Exchange Commission, he adds. "That's Washington—that's what people do there."

To compensate for the loss, Dechert, like other firms, practices lateral hiring. "You try to get the best people you can and hopefully some of those are people of color," he says. "It's a competition out there. There's not much to do except do a better job of holding on to people we have and recognize we have some strong people coming up the ranks."

So how do you hold onto what you have? Dechert recently hired an African American woman associate at the firm, Sharon Brooks, to be director of associate development. Francis points out that Brooks has begun surveying attorneys and putting together ideas for greater retention. "It's a continued investment in time," he explains. "The other partners and I have to make a commitment to spend the time to make this happen—getting to know people, making sure they feel good about their career paths."

This summer, the firm had a dinner series for minority lawyers in different offices, including the District of Columbia. "The purpose is to get everyone together to see there is strength in numbers and feel like a community," Francis explains. "My hope is if we can continue that community building, that will give us a foundation to build the critical mass we've been wanting to build."

While there has been a formal mentoring program at the firm for many years, Francis says he wants to help facilitate the relationships, and will work with Brooks to accomplish this goal. But he also recognizes the deeper issue. "The problem faced by most firms like us is the chicken-and-egg problem. How do you attract more people of color when you don't have as many people as you'd like?" he says. To answer his own question, he stresses that persistence and visibility are key.

"Like other firms, we've grown in the past couple years and have gotten some pretty strong lawyers of color with lateral hires. I'm hoping we can make some gains that way as well," Francis continues, adding that the firm attends job fairs sponsored by minority lawyer groups and reaches out to law schools. So, he concludes, not having partners of color in Washington, DC, "is not through lack of effort."

—Vernon Francis

Effort is part of the picture at Dewey Ballantine's District of Columbia office as well, according to Anna-Liza Harris, the hiring partner in DC who also is on the firm's diversity committee. Harris explains that one of the firm's mandates is to look into how to best retain and promote the women and minority attorneys hired. "Like many other international law firms, we do very well at recruiting," she says. "Our biggest problem is retention."

Why? She indicates that there are as many reasons as there are attorneys who leave the firm. But one solution the firm is implementing is strengthening and expanding its mentoring program. "We see that's a key to helping all of our associates, but with a special focus on women and minorities in developing careers and establishing strong ties to the firm," says Harris. "So through the natural progression of associates moving up through the ranks, we can try to stem the attrition and have a greater filling out of the women and minorities."

As conveyed by Harris, the firm recruits principally through its summer program. This year, 80 percent of Dewey's summer class in Washington, DC was minority, according to Harris. "We're very hopeful that through mentoring and other initiatives, we'll keep a larger percentage of them than we have in the past," she adds.

The firm also has a career development program for associates and has instituted a flex schedule system. One of the female partners already has taken advantage of it. She has changed her title to of counsel to pursue professional singing, Harris explains. "We're trying to institutionally be more nimble and responsive when questions and issues come up," she adds.

While DC firms with few or no females and minorities in the partnership ranks say it's a priority to raise those numbers, they recognize it takes time and effort. And one of the best processes is to think one at a time, says Harris. "Everyone is an individual and everyone has got their own particular issues, so I'd be hard pressed to say there's an overarching need or issue faced by any one group," she says. "When we see a candidate we want to pursue—whether it's recruiting them or encouraging them to stay—we're going to try everything we can think of to make that succeed."

Melanie Lasoff Levs is a freelance writer based in Atlanta, Ga. Information appearing in this article was compiled as of August 2005. Additions to staff made by firms after this period are not reflected in this article.

In the Trenches at Miller & Chevalier

By Melanie Lasoff Levs

With 110 attorneys, Miller & Chevalier in Washington, DC was the only firm of 101 to 250 attorneys whose National Association of Law Placement (NALP) law firm questionnaire listed no partners of color. When contacted, Managing Partner Sam Maruca conveyed that the firm recently made a lateral hire: a female minority partner. But, he admits, his firm has much work to do. "The firm has always had a diversity committee, but it's never been very active and certainly hasn't been proactive. We're historically a tax firm and people have hidden behind that and said there aren't any African American tax lawyers, which is, of course, not true," he says candidly, adding that since he became chair of the firm almost two years ago, he has made the committee a priority. "I've gotten more and more concerned about our statistics."

In the fall of 2004, Miller & Chevalier held a firm-wide retreat and asked representatives from five of their top clients and prospects to discuss diversity initiatives. "The message they gave us was, 'Hey, guys, you don't want to fall too far behind in this game because more and more of the in-house general counsel are women and minorities and they are putting outside counsel under the same microscope,'" says Maruca. The firm realized, he adds, "If we are going to compete, we better get our act together."

In March 2005, the firm hired an outside consultant to do an in-depth diversity assessment, which included surveying all lawyers and interviewing several throughout April. Maruca found that female partners and associates, as well as minority associates, named diversity of top importance, while white male partners and associates did not feel the same urgency. "This is not something 55-year-old white males have spent a lot of time thinking about," he adds.

Still, the consultant helped Maruca and upper management create and implement an action plan in the summer of 2005. It includes focus groups and informal meetings with partners on diversity, focusing on recruiting—including lateral hires and branching out for prospective hires, creating individual business plans for attorneys and core clients, and improving mentoring by offering a bonus pool for partners who are mentors. As explained by Maruca, the firm is focused on hiring one or two minority partners in the next year as well.

The process may be slow, but it is crucial, according to Maruca. "What I worry about is managing expectations," he explains. "We need to push this, but, by the same token, it's a question of acculturation. That takes fighting in the trenches for a long time to get it to work. But everyone has an obligation and we can't have anyone on the sidelines."

| Washington, DC Law Firms with No Partners of Color (Based on data supplied by the firms themselves to NALP in February 2005, for the 2005–2006 academic year.) | |

| Firms with 51 to 100 Attorneys (NOTE: Diversity & the Bar® chose to contact only firms with 51 to 100 attorneys for purposes of the article.) Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton Firms with 26 to 50 Attorneys Bryan Cave | Firms with 26 to 50 Attorneys (cont'd) Ivins, Phillips & Barker Firms with 11 to 25 Attorneys Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz *Did not return repeated telephone calls. |

From the November/December 2005 issue of Diversity & The Bar®