While “the sky is not falling,” a significant crisis in the legal profession is underway right now. By virtually any measure, things are not as good for attorneys as they have been in the past. The job market for recently minted attorneys is diminishing, while the number of lawyers is increasing. The fallout is not catastrophic; these young men and women are exceptionally gifted individuals who ultimately will enjoy successful careers. Nevertheless, current expectations are not being met and young attorneys are underemployed.

During the 1999 – 2000 academic year, 132,276 students were enrolled in 182 ABA-certified law schools in the United States. Ten years later, 152,033 students are enrolled in 200 ABA-certified law schools.1 Minorities accounted for 25,253 spots (19%) in 2000; by 2009, minorities represented 31,368 spots, (roughly 20.6%). Enrollment of minority students in law schools has risen steadily every year, a trend that shows no signs of slowing down in the recession.

What accounts for this phenomenon? Andrew Witko, a government contractor who is applying to law school, explains that, “for people who are tired of making $35,000 a year, or are just finishing up their undergraduate degree, law school provides an adequate way of sheltering themselves from the barren economic climate. Upon acceptance, law school students will need to pray that they find something after graduation that pays more than the $35,000 they made previously.” He hopes the job market for attorneys has recovered by the time he graduates, he shares.

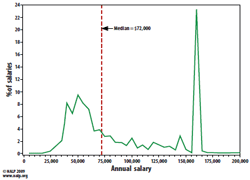

For many students, that may not be a reality. Salary distribution for the newest crop of law school graduates presents the most dramatic bimodal distribution of starting salaries to date (see graph this page). Throughout the 1990s, a recognizable bell-shaped curve describing the spectrum of starting salaries for new lawyers was the norm. Over the past decade, however, the distribution has deteriorated into two distinct camps—in which 23% percent attorneys make $160,000 at big firms, while 42% of attorneys earn between $40,000 and $65,000.2

These data are self-reported by new lawyers, and may disproportionally represent higher-paid lawyers who likely are more willing to share details of their salaries. The salaries of lawyers employed by “Big Law” have increased steadily over time, while the starting salary of those employed elsewhere (as represented in the graph in the peak on the left) has remained basically stationary. In previous distributions, a noticeable “elbow” of attorneys making a starting salary of $145,000; this group has since disappeared as a significant statistical group, as firms made $160,000 the industry standard. The median salary for a new attorney is $72,000, meaning half of all starting attorney salaries are less than $72,000. It is anticipated that recent developments will knock the sharp spike closer to that median.3

With law-school enrollments approaching 50,000 students per year, many observers believe that the market has become saturated. This scenario—a high number of graduates vying for fewer positions—may serve to reinforce a recruitment strategy governed by the myth of meritocracy. Traditionally, the legal profession has hired recent graduates under the philosophy that those who display superior achievement—or merit—through high law-school grades, coupled with class and lawschool rankings, should be rewarded with employment opportunities. An MCCA research report released in 2003, entitled The Myth of the Meritocracy: A Report On the Bridges and Barriers to Success in Large Law Firms, addressed the fact that, while these credentials may be acceptable measurements of performance in law school, they are not necessarily a good gauge of a student’s potential, are not valid indications of success or failure as a practicing attorney, and may disproportionately weed out minorities and women. With the job market for recent law school graduates drastically shrinking, reasonable concern exists that recruitment strategies limited to a “meritocracy” model may have an even greater chilling effect on recruitment of diverse young attorneys.

Source: Jobs & JD’s: Class of 2008, published by the National Association for Law Placement (NALP), 2009.

Several factors are coalescing to make this year particularly different for new JD holders. Long-term growth in the legal profession has lagged behind that of the broader economy since the late 1980s. The legal sector, after more than tripling in inflation-adjusted growth between 1970 and 1987, has grown at an average annual inflation-adjusted rate of 1.2% since 1988, or less than half as fast as the broader economy, according to Commerce Department data.4 Even during this period of modest growth in the legal sector, from the early 1990s until the mid-2000s, the top 100 firms doubled in size while partn profits were up 215%, according to American Lawyer.5

But those days seem like a distant past. For the first time since 1991, average profi ts per partner and revenue per lawyer dipped among the 100 top-grossing firms in the nation. Although a decrease in demand is partly to blame, law firms also are burdened by operating under an archaic hiring practice. Ordinarily, firms hire new associates two years in advance of their actual start date, making it impossible to react to market pressures. By offering jobs to graduates before the economy tanked, firms allowed the percentage change in headcount to exceed percentage change in profi ts, which resulted in less money for partners.

The combination of the Great Recession and the influx of new graduates means that 2010 is not the year many graduates would like to see on their diploma.

If summer associate hiring rates are any indication (and they are), the news is not good. Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, the highest-grossing U.S. law firm in 2008 with $2.2 billion in revenue, expects to hire less than half the number of summer associates this year (about 110) than the firm did in 2009. More than 95% of 2010’s summer class will be offered full-time positions and asked to defer their start dates until 2011, according to Skadden recruiting partner Howard Ellin.6

According to a 2010 survey produced by the National Association for Law Placement (NALP), the off er rate to summer associates for entry-level associate positions declined by more than 20%—from 89.9% in 2008 to 69.3% in 2009. Th is is by far the lowest offer rate measured since NALP began collected data in 1993. Similarly and not surprisingly, the acceptance rate for these offers jumped by nearly five full percentage points, to 84.5%, which is the highest acceptance rate ever recorded.7 To put it bluntly, fewer off ers are extended. If a law student has an offer on the table, he or she is going to take it.

The scenario gets even worse if attorneys are minorities. American Lawyer Daily measures diversity in the country’s top law firms with its annual Diversity Scorecard. In each of the previous nine years, the percentage of minorities has increased, rising from less than 10% in 2000 to 13.9% in 2008. In 2009, for the first time, that proportion dipped, to 13.4%.8

Perhaps the biggest question facing new graduates is whether the shift in the legal paradigm is temporary or permanent. One way to gauge the shift is by observing the actions of the law firms. Some short-term solutions that many firms are implementing include laying off associates, deferring start dates for new hires, reduced or eliminated second- and third-year programs for law students, and revised hiring schedules. Other firms are considering or implementing solutions with a longer-term focus. Strategies that could indicate a long-lasting change to the way lawyers are hired at big firms include reduced associate compensation, merit-based compensation, and increased training and mentoring for associates.

A recent editorial, published anonymously in the Harvard Law Record, laments the state of affairs for new graduates: “The dream of Biglaw is hard to let go. And after all, there isn’t necessarily any shame in wanting to make money. Some of the wealthiest Americans have been its greatest philanthropists … I don’t think we should be judged for wanting to be Biglaw associates with the money and power that it would have eventually brought.”9 Perhaps those pursuing a legal education should consider why exactly they are entering law school in the first place. Maybe that’s one of the primary lessons offered by today’s challenging circumstances. DB

Joshua H. Shields is the editorial assistant for Diversity & the Bar.

Note

1 American Bar Association (ABA), Total Minority J.D. Enrollment 1997 – 2008, available online at www.abanet.org/legaled/statistics/charts/stats%20-%2010.pdf (visited 3/10/2010).

2 National Association for Law Placement (NALP), Salaries for New Lawyers: How Did We Get Here? (2008), available online at http://nalp.org/2008jansalaries (visited 3/11/2010).

3 National Association for Law Placement (NALP), Jobs & JD’s: Class of 2008 (2009), available online at nalp.org/08saldistribution (visited 3/10/2010).

4 Amir Efrati, Hard Case: Job Market Wanes for U.S. Lawyers. WALL ST. J., 24 Sept. 24, 2007, available online at online.wsj.com/article/SB119040786780835602.html (visited 3/10/2010).

5 Aric Press and John O’Connor, Lessons of The AmLaw 100. THE AMERICAN LAWYER, May 1, 2009, available online at www.law.com/jsp/tal/PubArticleTAL.jsp?id=1202430183962 (visited 3/11/2010).

6 Cynthia Cotts and Carlyn Kolker, Skadden Arps Slashes Law School Hires for Summer of 2010. BLOOMBERG.COM, Aug. 25, 2009, available online at www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601103&sid=aQ4ik1Yd4C9Y (visited 3/10/2010).

7 NALP, Perspectives on Fall 2009 Law Student Recruiting (20010), available online at nalp.org/uploads/PerspectivesonFallRec09.pdf (visited 3/11/2010).

8 Emily Barker Diversity Scorecard 2010: One Step Back, THE AMLAW DAILY, Mar. 1, 2010, available online at amlawdaily.typepad.com/amlawdaily/2010/03/onestepback.html (visited 3/10/2010).

9 Anonymous, Unemployed law student will work for $160k plus benefi ts, HARVARD LAW RECORD, Mar. 1, 2010, available online at www.hlrecord.org/opinion/unemployed-law-student-will-work-for-160k-plus-benefits-1.1179172 (visited 3/10/2010).

From the May/June 2010 issue of Diversity & The Bar®